Each year when February rolls around, I think of Carter G. Woodson. During African American History Month, it is almost impossible to not be reminded of the amazing work of Dr. Woodson. When I see school-aged children reciting poems or reenacting events of significance for African American history, my mind irresistibly slips back to the man who, above all others, started it all.

Dr. Woodson was the first Harvard graduate born to enslaved parents and the second person of African descent to gain a doctorate from Harvard University, following W.E.B. DuBois. Woodson saw clearly the adverse effects of American culture and its educational system on the psyche of black children. During this period, classroom teaching guides often presented black people as non-existent or egregious caricatures that were naturally inferior to whites. School curriculum, represented through textbooks, contributed to the sense of self-hatred among black children, and helped propagate racial bigotry and the doctrine of white supremacy. As Dr. Woodson bluntly proclaimed, the curriculum taught black children that their “black skin was a curse.” In 1915, Dr. Woodson’s Association for Study of Negro Life and History was the first to advocate for a cultural competence curriculum, he advised that “approaching people’s education by utilizing their distinct cultural characteristics was a matter of common sense” (Woodson 1933/1998, p. ix).

In 1926, Dr. Woodson instituted “Negro History Week” to celebrate the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass. “When an individual or groups fails to teach or learn their culture,” he wrote, “over time their culture will be rendered nameless and faceless” (Woodson 1998, p.27). Woodson insisted that, if all students could hear and read about the contributions of African civilizations, they would have a greater appreciation of Black culture. Dr. Woodson also founded the Journal of Negro History (January 1916) for scholars and the Negro History Bulletin (October 1937) for teachers and schoolchildren. In 1976, at the bicentennial celebration of the United States, President Gerald R. Ford expanded Black History Week into a full month, stating that the country needed to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of African Americans in every area of endeavors throughout our history.” Today, Black History Month has reached global status and is celebrated in the United Kingdom, Canada, Nigeria, and many Caribbean islands.

The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), Woodson’s best-known work, introduced the conceptual framework of what is known today as culturally responsive pedagogy. Dr. Woodson argued that Black History teaching needed to be practical and relevant to students’ learning, and that education of any people “should begin with the people themselves” (p. 32). As he was of the view that the mere imparting of information does not constitute proper education, Dr. Woodson encouraged teachers to develop and implement a Black History curriculum that would yield tangible benefits for all students. Woodson wanted teachers to use critical and demanding activities that challenged the traditional racial narrative to help change students’ “present atmosphere” (p. 96). Furthermore, Woodson advocated for the inclusion of the teaching and analysis of African Diaspora into the study of Black History to increase its effectiveness.

Woodson, like few others, initiated and sustained a movement that provides a counter narrative to the negative image of African Americans that had been conjured up in the American cultural mindset. In his autobiography, Malcolm X stated that his reading of Woodson’s works while in prison was integral to the development of his political consciousness.

For Malcolm, Woodson’s scholarship was instrumental to his appreciation of “black empires before the black slave was brought to the United States and the early struggles for freedom” (p. 178). Woodson’s clarion call for black empowerment is compellingly vocalized in the rhythmically energetic refrain of James Brown’s 1968 hit “Say it loud, ‘I’m black and I’m proud.'”

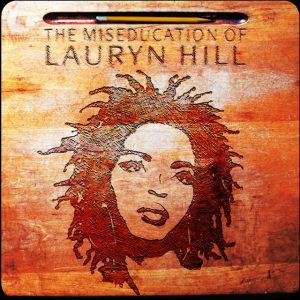

By invoking Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education in the title, the release of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill remix pays tribute to this great man’s legacy. Lauryn Hill is also widely praised for giving voice to black womanhood within the male-dominated world of hip-hop. In 2004, the United States Library of Congress selected the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill as one of 25 recordings to be inducted into the Library of Congress National Recording Registry due to their cultural, historical or aesthetic importance.

Afrofuturism

Reverberating the ancestral spirt of Dr. Woodson, Afrofuturism is currently dominating the pop culture and is continuing Woodson’s legacy of actively rejecting the hegemony of whiteness. Ytasha Womack, author of the seminal work Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, writes “Afrofuturism existed before it was called Afrofuturism.” Its elements are found in the pioneer work of jazz musician Sun Ra during the 1960s, with his custom-made electric space suits, as well as in the futuristic stage performances of Parliament Funkadelic and Earth Wind & Fire in the 1980s.

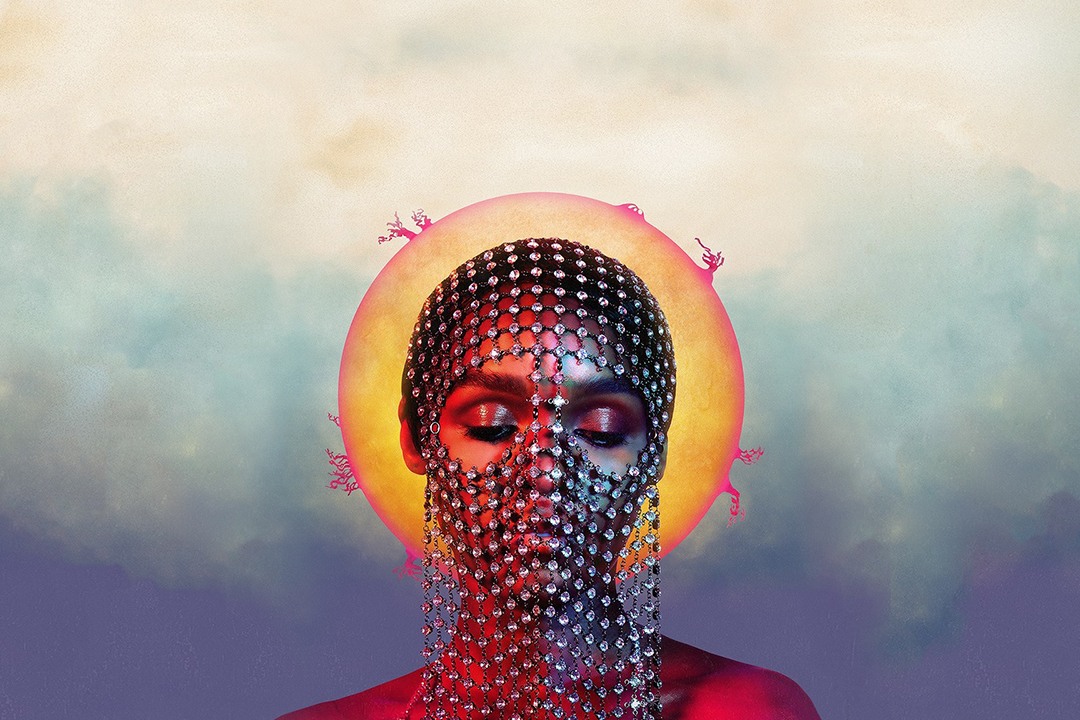

Coined by cultural critic Mary Dery, Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic at the intersectionality of race and technology, combining science-fiction, technology, and fantasy to explore the key aspects of Black Diaspora, as well as the journey and history of people of African descent in the world. Elements of Afrofuturism are included in the work of science-fiction novelist Octavia Bulter, Jay-Z’s “Family Feud” music video, and the imagination of sing/songwriter Janelle Monáe, who, as the Washington Post describes, “brandishes the acetylene torch for radical Afrofuturism.”

By most accounts, the movie Black Panther, which achieved runaway box-office success and rapidly emerged as a genuine cultural phenomenon, is the highest-profile Afrofuturist artform to penetrate the public consciousness. Black Panther is unlike any Hollywood film we’ve ever seen, as it draws upon a deeply rooted culturally relevant viewpoint developed by Dr. Woodson when he founded Negro History Week nearly a century ago. In a recent PBS Newshour interview, Ruth E. Carter, the movie’s Oscar-winning costume designer, describes her approach to the setting of the fictional Wakanda. “We based it on so many rooted ideas and cultural things, that people feel they can actually buy a ticket and fly to Wakanda.” She found inspiration from various traditions, cultures, and indigenous people across the African continent–the Dogon of Mali, the Tuareg in North Africa, and the Himba of Namibia. One of her favorite costume designs is the 3D printed intricate crown and shoulder mantle created for Ramonda, King T’Challa’s mother.

Constructionism

Constructionism is a theory of education developed by Seymour Papert, justifiability known as “the father of the maker movement.” Renowned mathematician, co-creator of the Logo programming language, co-founder of the Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT, and a founding faculty member of the MIT Media Lab, Papert’s constructionism brings creativity, tinkering, exploration, and problem-solving to the vanguard of the learning process. Building on his constructionist framework, the SCOPES-DF lesson collection offers playful classroom environments where students become creators and makers, designers of objects meaningful to them, and producers of tangible artifacts, which they make using Fab tools. This type of hands-on/minds-on discovery-based learning is critical not only in and of itself, but also as a conduit to learning STEM subjects. It is also vitally important for the development of 21st century skills, such as curiosity, creativity, artistic expression, collaboration, communication, problem-solving, critical reasoning, and design thinking.

Constructionism is a theory of education developed by Seymour Papert, justifiability known as “the father of the maker movement.” Renowned mathematician, co-creator of the Logo programming language, co-founder of the Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT, and a founding faculty member of the MIT Media Lab, Papert’s constructionism brings creativity, tinkering, exploration, and problem-solving to the vanguard of the learning process. Building on his constructionist framework, the SCOPES-DF lesson collection offers playful classroom environments where students become creators and makers, designers of objects meaningful to them, and producers of tangible artifacts, which they make using Fab tools. This type of hands-on/minds-on discovery-based learning is critical not only in and of itself, but also as a conduit to learning STEM subjects. It is also vitally important for the development of 21st century skills, such as curiosity, creativity, artistic expression, collaboration, communication, problem-solving, critical reasoning, and design thinking.

As a proud alumnus of Howard University, where Dr. Woodson once served as the Dean of Liberal Arts, and as a current member of the Fab Foundation team, it has been one of my highest honors to participate in the development of the SCOPES-DF lesson collection that can be used in K-12 classrooms, Fab Labs, or Maker Spaces during Black History Month, or at any other point throughout the academic year. It is equally gratifying to present digital fabrication lessons that combine Dr. Woodson’s culturally relevant evidence-based strategies embedded within the ideas of Seymour Papert’s constructionism.

Fab Learning with SCOPES-DF Lessons

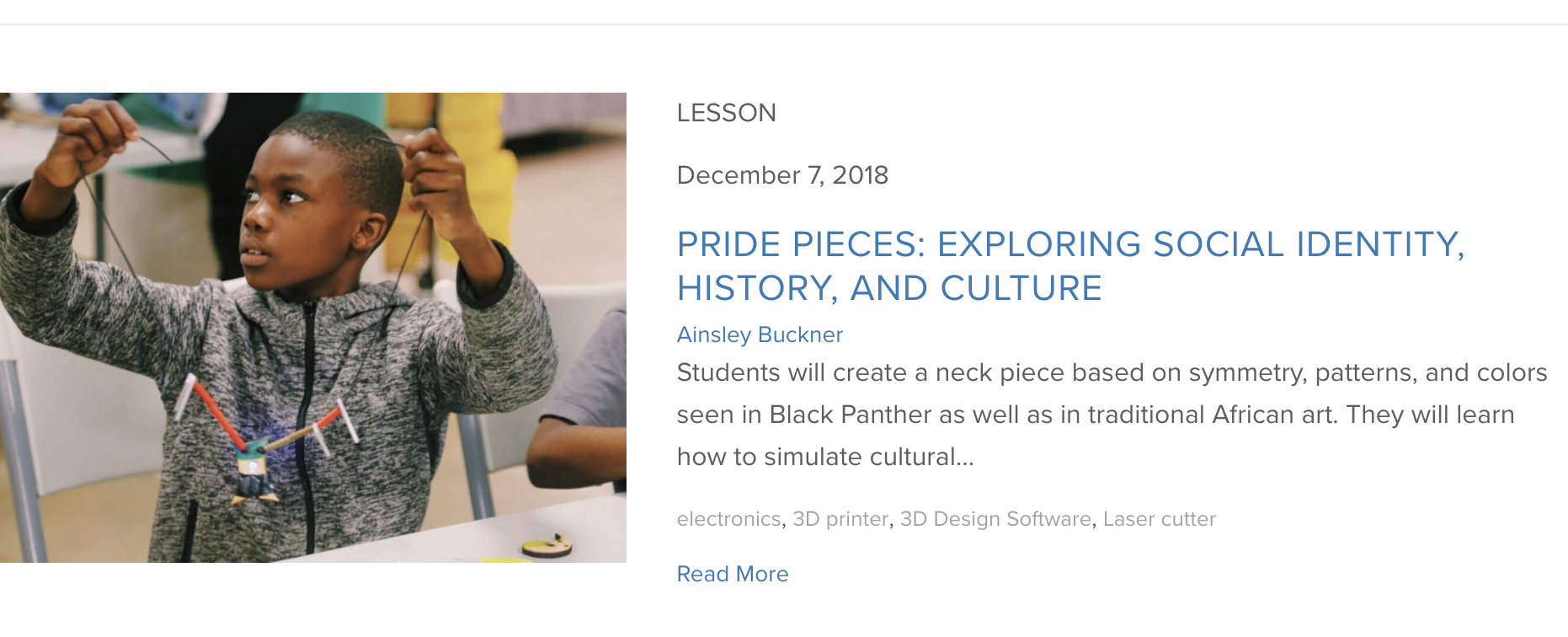

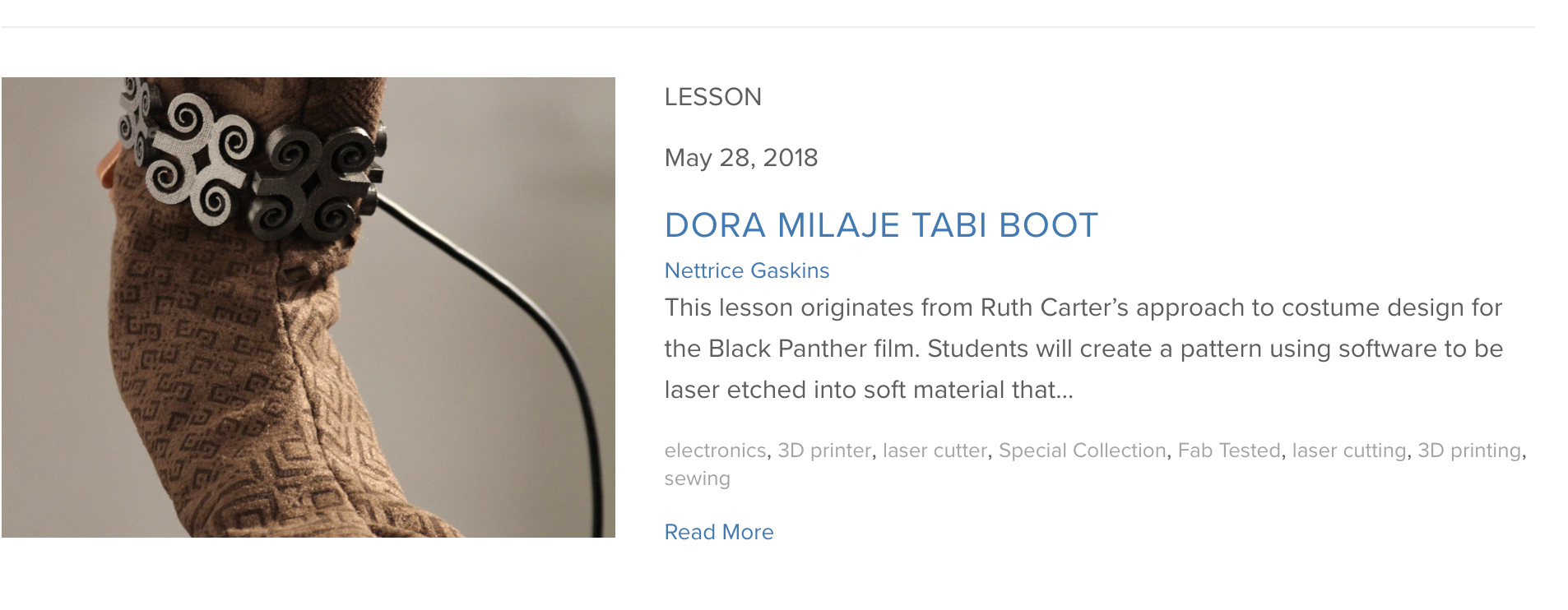

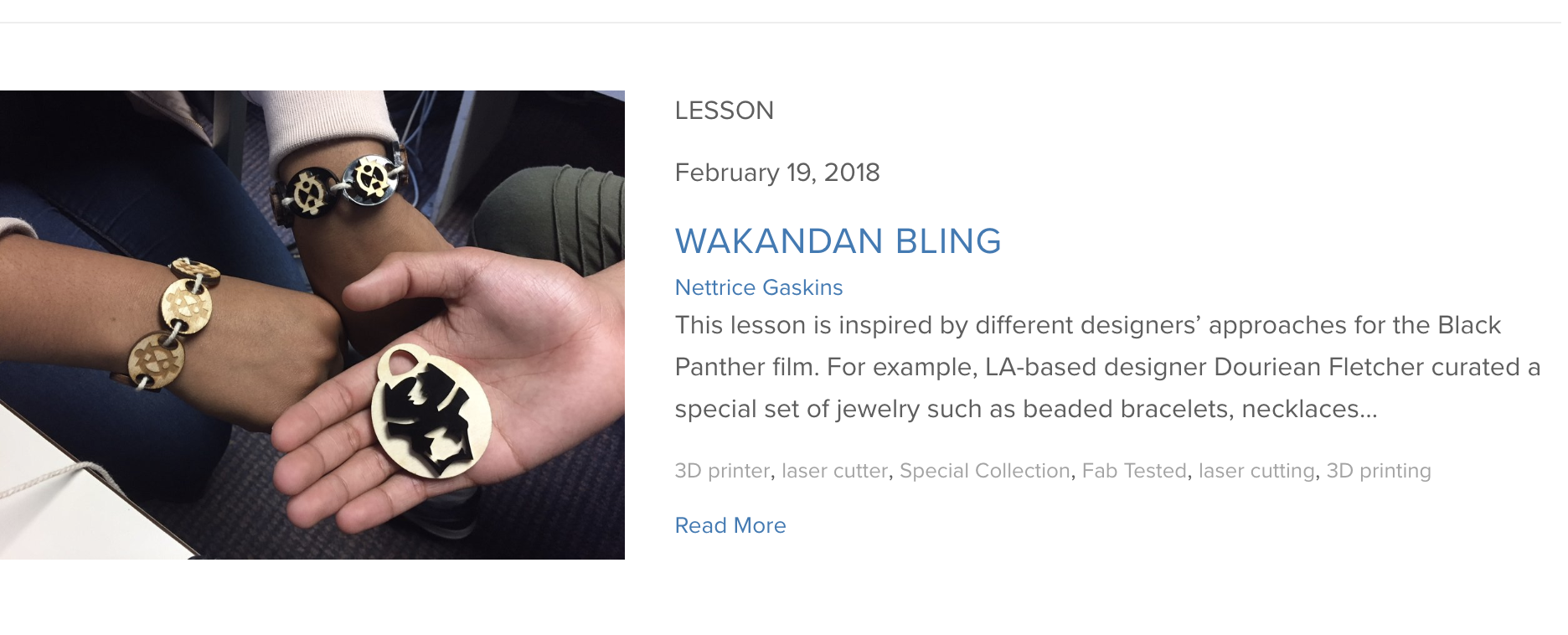

The SCOPES-DF website provides culturally relevant lessons that engage students in hands-on learning opportunities and other foundational elements of digital fabrication. Each lesson offers a simple yet effective means to engage student thinking, promote discussion and collaboration, and encourage creativity, while prompting students to use a critical lens in applying Fab practices and techniques. In order to ease students into the digital fabrication, scaffolding in the form of guided questions and teacher notes is provided. Each lesson task or activity is broken down into small steps, whereby learners are given one instruction at a time. Check out these examples:

Pride Pieces: Exploring Social Identity, History, and Culture

DIY Adinkra Symbols with 3D PrintinG

Dora Milaje Tab Boot

Wakandan Bling

Wearable Tech in Afrofuturism

Music & 3D Modeling: From James Brown to Architecture

What’s Next?

Check out these lessons and then make your own and share it with our community of Fab Learners. Breaking down complex processes into simpler steps makes Fab learning goals more attainable – e.g., see the Fab I Can Statements. Furthermore, each lesson in the SCOPES-DF collection reinforces Common Core/Next Generation Science Standards pedagogical shifts by incorporating the digital fabrication iterative design process.

References

- Womack, Ytasha (2013). Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. Lawrence Hill Books, Chicacgo

- Woodson, Carter G (1998). The Miseducation of the Negro. Trenton, NJ. African World Press

- X, Malcolm and Alex Haley (1965). The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Grove Press, New York, NY

Tagged: Black History Month